Property-based Testing Patterns

In his LambdaJam 2015 presentation on How I learned to stop unit testing and love property-based testing, Charles O’Farrell covers some standard patterns you should use with property-based testing. These patterns turned out to be somewhat of a guiding light for me when writing property-based tests with Scalacheck.

I found some of the names of the patterns hard to remember so I’ve renamed them below to make it easier for me to recall the pattern they refer to. I’ve also included the alternate names each pattern is referred to by, so feel free to learn the name that most resonates with you. The images used are from the F# for fun and profit (FFP) blog and is where most of these patterns originate from.

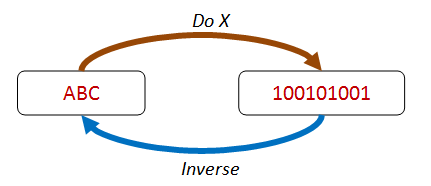

1. Round-tripping/Symmetry/There and back again

The basic premise is that you convert some value to another value and then convert it back to the original value. Serialization is a typical example. Parsing text to an object and then writing out the object back to the original text would be another.

One thing to keep in mind is that the conversions can’t be lossy. If you loose information one way, then you can’t introduce it back when going the other way.

For example if you are trimming spaces in some text before converting it to an object, when converting back from the object, you will not know whether there were extra spaces in the input or not.

final case class Name(value: String)

val input = " Tom Jones "

Name(input.trim).value == input //failsOne way to get around this is to always convert the input to a form that does not lose any information when converted back from the previous output. In the above example it could be that you trim the input text when checking for equality. That way you never have to worry about reintroducing spaces. This could lead to some false assumptions though.

val input = " Tom Jones "

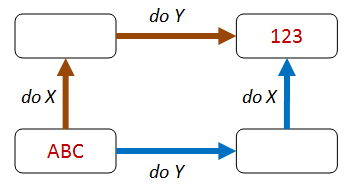

Name(input.trim).value == input.trim //passes2. Commutativity/Different paths, same destination

The basic premise is that changing the order of some operations should not change the final result.

An example would be adding the same value to every element of a List and then sorting it should be the same as sorting the list and then adding the value to each element.

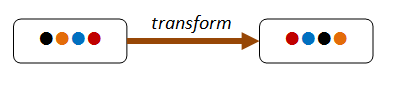

numbers.sorted.map(_ + 10) == numbers.map(_ + 10).sorted3. Invariants/Some things never change

The basic premise is that with these properties, performing some kind of operation does not change a given property of the test subject.

Common invariants include:

- The size of a list should not change after a map operation.

- The contents of a list should not change after a sort operation.

- The height or depth of something in proportion to size (eg. after balancing trees).

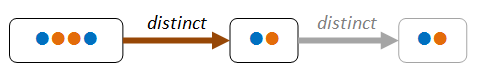

4. Idempotence/The more things change, the more they stay the same

Basically performing an operation once should be the same as performing an operation twice. An example would be sorting a list more than once should be the same as sorting the list once.

numbers.sorted == numbers.sorted.sorted.sorted5. Induction/Solve a smaller problem first

FFP explains it as:

These kinds of properties are based on “structural induction” – that is, if a large thing can be broken into smaller parts, and some property is true for these smaller parts, then you can often prove that the property is true for a large thing as well.

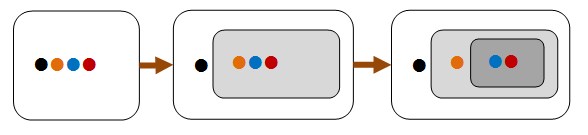

In the diagram below, we can see that the four-item list can be partitioned into an item plus a three-item list, which in turn can be partitioned into an item plus a two-item list. If we can prove the property holds for two-item list, then we can infer that it holds for the three-item list, and for the four-item list as well.

Induction properties are often naturally applicable to recursive structures (such as lists and trees).

6. Blackbox Testing/Hard to prove, easy to verify

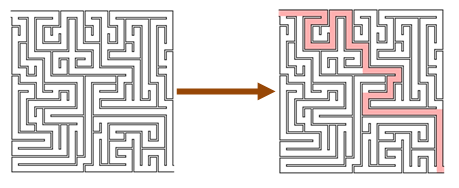

These are properties that are hard to compute but easy to verify. An example would be calculating the nth prime number. It’s easy to verify the answer if you already know the nth prime. In the example below, finding a valid route through a maze is hard - verifying it is easy.

7. Comparison with another implementation/Test Oracle

The premise is that you verify your property by running the same test against another implementation of the algorithm. An example is to compare the result of a parallel or concurrent algorithm with the result of a linear, single-threaded version. Another example could be verifying your shiny new json parser against an existing parser implementation for the same inputs.

Something to keep in mind

In addition to the above patterns, the properties you choose should actually fail if there are errors. This sounds too obvious to be mentioned but here’s an example that should fail but doesn’t:

Given a sort implementation for a list that returns the original list unchanged:

list.sort == list.sort.sort

list.sort.length == list.lengthThe above properties pass.

The following property correctly fails the above implementation because it ensures that each element in the list should be greater than or equal to the preceding element:

list.sort.sliding(2).toList.forall { case List(f, s) => f <= s }Property-based testing requires that you think a lot more about your code. You need to identify the properties that are true and false for it. The result is a lot more confidence in your code than had you just unit tested it.

Some additional resources: